- Home

- Cosgrove, Stuart;

Memphis 68 Page 9

Memphis 68 Read online

Page 9

King was possessive about the blues and frequently scolded Stax’s younger soul musicians for having deserted what he considered to be the true path of black music. The session musician Sandy Kay witnessed his unique style close up. ‘I did Albert King’s tracks in B studio with James Alexander, Willie Hall and Michael Toles,’ he wrote in his diary about life at Stax. ‘Those were the very first sessions cut in B studio – it was recently built, and was actually still under construction. Albert bitched at all of us because we were too young to understand the blues. The air-conditioning didn’t work yet and it must have been a hundred degrees in there . . . When the session started, Albert was wearing a beautiful pastel suit, matching hat, tie, vest, shoes, handkerchief, everything. He progressively took off almost all of his clothes, and ending up sweating rivers in his underwear and socks.’

According to jazz musician Wynton Marsalis, the blues was principally about love gone wrong rather than sociology. This is particularly true of King, who, after joining Stax, fitted easily into their internal songwriting culture, which wrenched tears from a million failed love affairs. ‘Everything comes out in blues music: joy, pain, struggle,’ Marsalis once said. ‘Blues is affirmation with absolute elegance. It’s about a man and a woman. So the pain and the struggle in the blues is that universal pain that comes from having your heart broken. Most blues songs are not about social statements.’ It was a powerful idea but one that had an upward struggle to be taken seriously; the blues and poverty were so ingrained in the minds of many musicians. The Chicago DJ Big Bill Hill observed that ‘the blues had something to do with that bastard of life most black people want to forget. They don’t want to be reminded of sad memories.’ While that may have been true of the retreating voices of the old bluesmen of the South, it was not true of the new generation of devotees; Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield, Eric Clapton, John Mayall and even the Rolling Stones idolised the blues, believing it spoke to universal suffering and a new kind of teenage alienation.

King himself became the bad-sign mentor of at least three generations of guitarists, including Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Rory Gallagher. It was his Stax releases that helped him to connect with a new and vibrant young audience, particularly the countercultural hippies of San Francisco who tapped into the poor, alienated and political undercarriage of blues music. King was booked to open Fillmore West, the showcase for new music in the city’s old Carousel Ballroom, which for most of 1968 operated as a laboratory collective of the west coast’s most experimental bands such as the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service. On stage he cut a strident visual style and was often joined by Jimi Hendrix and John Mayall. He returned regularly, and became a Fillmore West fixture with a reputation that spread like wildfire among innovative and informed guitarists.

It was an era when festivals had begun to appear on the counter-cultural map. The long-established Newport Festival, which pioneered folk and jazz, had witnessed its first culture shock in 1965, when Bob Dylan broke with troubadour tradition and played with an electric guitar accompanied by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. In the summer of 1967, Otis Redding had stormed to success at California’s Monterey Pop Festival and instantly transformed his reputation from southern soul singer to international star. Woodstock was only a summer away, and still hidden from view, virtually invisible outside Memphis, a small cadre of local music obsessives were slowly building the Memphis Country Blues Festival, an annual summer event that defied musical categorisation, ranging from deep southern soul to bar-room blues and hardcore rock funk. It laid the first stone in a lengthy building project that would transform Memphis into the most successful ‘music tour’ city in the world.

Wayne Jackson witnessed the journey close up. The Stax trumpeter once claimed that Albert King, despite his flaws, was the greatest of his kind: ‘I think that Albert King was probably the most influential guitar player that ever lived. Every time you hear a rock-and-roll guitar player, he’s playing Albert King licks. He’s a guitar player who will never die.’ But die he did, and in circumstances that were in many ways reflective of his uniquely bizarre life. According to Steven Seagal, King’s demise was dramatic. Realising he was having a heart attack, King asked a girlfriend to drive him to a Memphis hospital. She drove to the parking lot, stole his jewellery, and left him to die there, only a few hundred yards from the emergency ward.

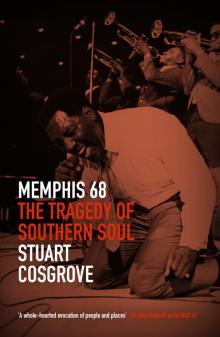

SOUL BROTHERS. Young teenagers are attracted to the downtown protests and join a picket line during the week that Larry Payne is killed.

Courtesy of Preservation and Special Collections, University of Memphis

LARRY PAYNE’S DAY OFF SCHOOL

28 March

Larry Payne was tall, thin and lithe. Superficially, he was like a young Wilson Pickett, but that’s where the similarities ended. Pickett had played in the fast lane of soul music; Payne had yet to have a life. He was barely sixteen years old, an impetuous teenager with no great love of school, and any ambition he did have was restricted by his race and his surroundings. Payne was an irregular pupil at Mitchell Road High School in the Southside, and when he did attend classes it was always with one eye on the door. His parents had separated, and so he spent most of his time waiting for buses and moving between their two homes. Divorce meant a fragmented family but it had one hidden benefit: he had two groups of friends – his schoolfriends at Mitchell and a gang of excitable teenagers on the Fowler Homes Project on Fourth and Crump Boulevard, only ten blocks south of Beale Street, where his mother Lizzie had an apartment. Her home was in the middle of a low-income neighbourhood, where young people had the streets and not much else, but for Payne, impressionable and desperate to be liked, it was a much more exciting place than learning the states of the union by rote at his school.

Payne liked soul music at a time when the music was changing profoundly. He had taken to the early music of Black Power, especially the Impressions’ ‘We’re A Winner’ and James Brown’s hit ‘Say It Loud I’m Black And Proud’, both of which were on heavy rotation locally and unambiguous anthems of black pride. Out in the ghetto projects, a new mood was percolating. For some it was impatience that the pace of change was too slow; for others it was a question of refusing to be deferent. Many black people, particularly the young, were no longer willing to tolerate the bias and hierarchy of the past. The city that Mayor Henry Loeb thought he was in control of was tearing apart at the seams.

Stax were negotiating with a tiny Detroit label called Tuba to acquire the rights to Derek Martin’s implicitly political ‘Soul Power’, a song they subsequently released on their subsidiary label Volt. The B-side, ‘Sly Girl’, had all the cadences of a Motown dance hit, except for Martin’s R&B growl. The first use of the term ‘Black Power’ as a political slogan was by Stokely Carmichael at a speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, in June 1966, after the shooting of James Meredith. But the term was not yet in everyday usage, and would not appear on a record until late 1968, when an obscure Long Island funk musician, James Coit, released a hectic and hectoring dance record simply called ‘Black Power’. Soul was in flux again.

Like many of his age, Payne looked up to older boys, especially those who played fast and loose with life. He hung out with a street gang who the police referred to as the ‘Beale Street Professionals’, although that was never their adopted name. He had also met members of the Invaders, a group of activists who had leafleted Mitchell High School as part of a city-wide campaign to recruit school students, encourage their support of the Sanitation Workers Strike, and urge them to take more militant courses of action. By early March 1968, the Invaders had a strong base in Riverside and further into the Southside, and were targeting the major high schools in an attempt to influence the curriculum to teach black history in the classroom. A generation had been born that was refusing to accept the glacial pace of civil rights and impatient for change. James Brown, who had played to a rumbustious crowd at the Mid-South Coliseum in January, had been forced to do several encores of ‘Say It Loud I�

��m Black And Proud’, a song that had become a street anthem for the emergent Black Power teenagers. But it was neither the Godfather of Soul nor the restless youths of the Memphis Invaders that determined Payne’s short life. His fate was to become inextricably bound up in the crusades of the most famous civil rights leader of all time – Martin Luther King Jr.

As Payne ran the streets between Beale Street and the Fowler Homes, John Gary Williams had come home. The Stax soul singer had returned from Vietnam restless and transformed. Since 1964, Williams had been the lead singer with Memphis harmony group the Mad Lads and had taken an enforced break from his singing career when he was drafted into the military. He was keen to return to singing and a career at Stax Records, but a switch had gone on in his mind, and he had witnessed first-hand a war that not only changed him but changed a generation. Williams was not alone. Another member of the Mad Lads, William Brown, the Stax singer-songwriter William Bell, and Raymond Jackson from the Stax songwriting triumvirate We Three Productions had also gone to Vietnam, surviving on basic military supplies and the occasional box of treats mailed out from their local record store by the matriarch of Satellite Records, Estelle Axton. Each week, someone returned home and another was drafted. In the month that Williams returned to Memphis, another contemporary musician was sent to Vietnam. Archie ‘Hubby’ Turner, a keyboard player at Hi Records and relative of studio boss Willie Mitchell, was drafted into the US Army and despatched to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, for basic training, where the recently conscripted Jimi Hendrix and yet another Memphis musician, Stax songwriter Larry Lee, formed a makeshift R&B band.

Williams arrived home from Vietnam in January 1968 to find the city he had grown up in facing a year of unprecedented political turbulence. The Mad Lads were from Memphis but not of it. Their sound owed more to the northern doo-wop cities of Philadelphia and Baltimore, and they traded in matching suits, shared harmonies and descanting love songs. John Gary Williams, William Brown, Julius Green and Harold Thomas had grown up together and were students at Stax’s unofficial academy, Booker T. Washington High School, where they were known initially as the Teen Town Singers and then, briefly, the Emeralds. It was the Stax publicist and sometime songwriter Deanie Parker who helped to shape their unique identity. ‘They were young, they were mischievous, and that’s where they got their name from. When kids know they are getting under your skin, they turn up the heat, and that’s what they did,’ Parker claimed. Their name was inspired by their rough hoodlum edges and a nod to local DJ Reuben Washington, whose Mad Lad radio show on Radio Station KNOK-970 out of Dallas-Fort Worth reached out to urban teenagers as far away as Memphis. Washington was a local boy and a Stax enthusiast who had been the first to play Booker T. and the M.G.’s ‘Green Onions’ (1962) on heavy rotation, and was generally credited for its success.

By the mid sixties, the Mad Lads had enjoyed some tentative signs of success with R&B hits ‘Don’t Have To Shop Around’ (1965) (an answer record to the old Smokey Robinson and the Miracles standard ‘You Better Shop Around’), ‘I Want Someone’ (1965) and ‘What Will Love Tend To Make You Do’/‘I Want A Girl’ (1966). None of them crossed over to the predominantly white pop charts but they gave the Mad Lads a strong local following in Memphis, and down into the Deep South.

As the Mad Lads appeared to be prospering, the US military had launched Operation Prairie to attempt to eliminate the North Vietnamese Army. An army recruitment drive swept through the Memphis projects like a gale-force wind. Draft board letters landed at the South Memphis homes of John Gary Williams and William Brown, and the next phase of the group’s recording plans was put on hold. Within a matter of weeks, as Williams and Brown were conscripted, new singers were recruited to fulfil live shows, and the original nucleus of the group was despatched to basic training, en route to the battlefields of Vietnam.

Williams served in the malaria-ridden jungles of Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division. He was often sent on Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) missions along the Cambodian border. From March of 1967 until January 1968 he was in Vietnam during the first weeks of the infamous Tet Offensive, a series of fierce attacks on cities throughout South Vietnam. Although US forces managed to hold off the attacks, half a million troops were besieged in set-piece battles in and around Khe Sanh in Quang Tri province, with damaging consequences. More than 500 GIs died in February 1968 alone. A disproportionate number of the casualties were black and had been conscripted from inner-city neighbourhoods in Detroit, Chicago and Memphis, as well as the dirt-poor farming communities to the south of the city. News of such heavy casualties shocked the American public and further undermined support for the war.

Williams returned with eye-witness evidence of the chaos of Vietnam. Throughout his service his division faced intense combat. ‘These guys were hardcore,’ claims Gary O’Neal, an LRRP contemporary of Williams. ‘This wasn’t run anything like the regular army. There was basically only one rule, do whatever you had to do to survive. Most of the time there was nobody looking over our shoulders, nobody telling us what to do or how to do it, no one giving us any bullshit about uniforms or military procedure. We lived for the mission, and . . . the more time any of us spent in the field, the farther away we got from any type of normal behaviour. To survive out there in the jungle, fighting an enemy who understood the environment, we went native.’

Williams returned a changed man to a city that seemed incapable of change. Memphis had an estimated 90,000 black teenagers; fifty-two per cent of the city’s high-school population, they were the core market for Stax records but faced challenging times in the local job market, where the military, unemployment or manual labour were the most common experiences. Almost every black high school in the city witnessed student unrest in 1968. Booker T. Washington High School fought a campaign against local railroad companies after deaths and injuries occurred outside the school grounds, at a spot where seven different rail tracks merged. Trains frequently blocked the crossings for up to thirty minutes at school assembly time, so students regularly clambered over the top of the carriages or, more dangerously, under the wheels of the stationary trains. Rail deaths were racking up. In 1968 local newspaper the Memphis Press-Scimitar estimated that in recent years up to 1,700 people had died, mostly in crashes brought about by cars trying to jump the crossings, but schoolkids had also been killed, caught out by the sudden movement of freight trains. Local journalist James R. Reid rode in the cab of Frisco 134, a freight train from Tennessee Yards, and described a scene of terrifying risk. ‘As we moved through Memphis,’ he wrote, ‘we saw car after car, truck after truck, zoom across our path. The killing of motorists at grade crossings has become the greatest concern of the Frisco safety division.’ High-school protests were igniting elsewhere across the city. Safety at train crossings was a common complaint, discipline was another, but so, too, was the curriculum and the lack of awareness of black history. This young generation were no longer willing to tolerate their journey from slavery to social discrimination being airbrushed out of history. Prominent among the wave of student pressure groups, social organisations and street gangs were the Invaders, a collection of young radicals in their late teens and early twenties who felt that the Christian ministers for civil rights were too accepting of the slow pace of change. They were described by the police as a street gang, their dynamic name gave that impression, and they were catalogued by the FBI in what was inelegantly called the ‘Rabble-Rouser’ index, but the Invaders were much more complex than that; they were mostly the young and politicised, students, disenchanted war veterans, welfare workers and the unemployed.

After their discharge from the military, Williams and Brown were told by the current members of the Mad Lads, Julius Green and Robert Phillips, that they no longer wanted Brown back in the group. It was a body blow to the returning veterans, and as a compromise Stax hired Brown to pursue his interest in electronics. He came to be the first black recording engineer in the Memphis studio system. In a stand-off with the new

Mad Lads, Stax co-owner Jim Stewart forced them to reinstate Williams, who in turn was glad to be back but less devoted to the group’s origins in romantic harmony soul. Williams had been radicalised in Vietnam and now saw his city in a very different light. He befriended other returning veterans, among them John Burl Smith, a Black Power activist with links to the Socialist Workers Party, who in 1967 had formed the Black Organising Project (BOP), an influential street-level political party loosely associated with the Black Panthers, but more commonly known in the city as the Memphis Invaders. Like Williams, Smith had been shell-shocked at the indifference he faced when he came home from Vietnam. ‘When I returned, I really wasn’t into Black Power,’ he once said. ‘I was an American who had just served my country, and I was expecting my country to be appreciative.’ But he faced bleak opportunities, struggled to find work, and lived in a poorly constructed, federally funded low-rise apartment complex on Hanauer Street in the Riverside neighbourhood, near his old school, Carver High.

Memphis 68

Memphis 68