- Home

- Cosgrove, Stuart;

Memphis 68 Page 26

Memphis 68 Read online

Page 26

John Gary Williams’ trial attorney was a fascinating character in his own right. A well-liked figure on the Memphis music scene, Seymour ‘Sy’ Rosenberg had watched Stax grow from its hillbilly infancy to global success. Music writer Rob Bowman described him as ‘a cigar chomping, somewhat portly musician/lawyer with a well developed sense of humour’. Rosenberg had watched the Memphis music scene professionalise from close quarters. In the fifties, he had been a competent trumpeter in Sleepy-Eyed John’s band with Jim Stewart, and subsequently invested in a rival recording studio, Chips Moman’s American Sound Studio. As soul music surfaced, Rosenberg became a father figure to the generation of garage bands who grew up in the wake of Beatlemania and was an entertainment agent for the unconventional Rufus Thomas and, later, for country music star Charlie Rich. He even launched a local label into the burgeoning Memphis independent scene, Youngblood Records, and recorded Isaac Hayes’ debut single ‘Laura We’re On Our Last Go Round’ back in the days when Hayes was a young protégé who had been talent-spotted on a local radio show on WDIA. Rosenberg was a man who preferred conciliation to brutal argument and he was a key negotiator in the days when the Stax family split nearly brought the company to its knees. He acted as a lead attorney in Estelle Axton’s legal battle with her own brother and managed her eventual departure from the company.

It was probably through Axton that John Gary Williams came to hire Rosenberg in the first place. She had remained friendly with Williams since his return from Vietnam and was more tolerant than her brother of Stax artists embracing politics. Al Bell also shared many of Williams’ political views and it is quite possible, although never confirmed, that the Stax management underwrote Williams’ defence costs. Ultimately it was Rosenberg who managed to mitigate the threat of a lengthy jail sentence. He was acutely aware that, in the final analysis, all cases have to find a point of compromise, one where the parties will agree – or agree to disagree – and seeing the evidence stack up against Williams, he advised his client to show some penitence and not to unduly alienate the jury.

By 1968 up to twenty members of the Memphis Invaders were being held at the Shelby County Penal Farm – a mixed bunch of hardened political activists, street criminals and ghetto kids. The FBI’s COINTELPRO project and undercover Memphis police officers, led by Agent 500, had relentlessly targeted the group, regularly charging them with crimes relating to drugs and prostitution. While there was indeed an Invaders pimp corps working on the corners of Vance and Hernando near Beale Street, it was unusual for the group either to advocate or tolerate sex crimes. Coby Vernon Smith, a former member of the Invaders who was already under FBI surveillance when he first met Williams, has since described the Invaders as a product of their time and the unprecedented radicalism of 1968: ‘We were, in effect, mostly young men who had resisted the war. Some were veterans who had been to Vietnam. And for the most part, we were the underprivileged youngsters who were talking simply about being recognized as men ourselves. In fact, we had spent over a year organizing in Memphis, and we hoped that some of our attempts to organize encouraged the sanitation workers to go ahead and take the stand that they took. We welcomed this kind of challenge to start speaking up. We were at that time mostly young Black Power advocates who thought that the numbers and the energy and the synergism of the whole community, the whole South – the whole country, for that matter – dictated that we step up and speak up. We were traditional organizers, for the most part – young and foolish, perhaps, arrogant and obnoxious, in many respects. We just didn’t look the part that they wanted us to look. None of us were ministers. So we didn’t fit into the strategic mould that they wanted.’

And so, for a second time, John Gary Williams’ career was disrupted. First, his military service in Vietnam, and then a spell working in the sun-baked fields of the Penal Farm. During incarceration, when he continued to write songs and read voraciously, he began to imagine a solo career far beyond the harmony soul of the Mad Lads. He stayed in touch with Stax and in turn they stood by him. On his release he returned to his second home, the studios on East McLemore, where he discovered that the city, the studio and the times had changed dramatically. There was a more intractable political mood.

At the time of his release, Stax were mining a tiny seam of gold, deconstructing pop classics. Isaac Hayes had dismantled and rebuilt ‘Walk On By’ and ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’, and Williams brought out a haunting version of George Harrison’s ‘My Sweet Lord’ and a strident reworking of the Four Tops’ song ‘Ask The Lonely’. But it was one self-penned single that stood head and shoulders above those creative cover versions. In 1973 Williams recorded one of Stax’s greatest-ever songs, ‘The Whole Damn World Is Going Crazy’. Heavily influenced by the concept soul of the late sixties, especially Marvin Gaye’s classic social commentary ‘What’s Going On’ and the Temptations’ view of a confusing world, ‘Ball Of Confusion’, ‘The Whole Damn World Is Going Crazy’ was a song written from the depths of an incarcerated mind, describing a world of discrimination, gun crime and a city engulfed in hate. It was a song that spoke of the dark and confused forces that engulfed Memphis at the time, and it remains one of soul music’s unsung classics – a sign-of-the-times message that few have bettered.

The album from which the single was taken makes vivid the change Williams had undergone. On one side he is pictured in a purple stage suit adorned with bow tie, sitting by a dressing-room mirror about to go on stage. It is the kind of image that many great singers such as David Ruffin or Teddy Pendergrass might have posed for. But the image on the reverse side sees him staring into another mirror, in a fully grown afro, bare-chested in a distressed denim jacket sawn off at the shoulders, Memphis Invaders-style. It is a powerful image of the soul singer: first as romantic and then as street revolutionary.

John Gary Williams is back living in Memphis; he reformed the Mad Lads and performs regularly on the southern soul circuit. Fellow Invader Coby Smith completed his doctorate and is still active in Memphis community politics as a councilman for the city’s Ward 7. Charles Cabbage died in 2010 after years of diabetic-related illnesses and John Burl Smith, one of the original Invaders, has retired and now lives in Atlanta.

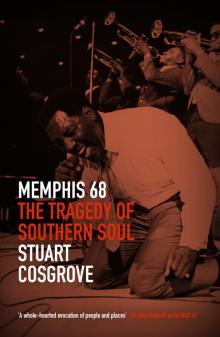

Black Power salute. Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico Olympics, October 1968.

© World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

BILL HURD’S FASTEST RACE

16 October

Bill Hurd was the fastest young man in Memphis. He proved it time and time again, on the sidewalk outside his home, at school competitions, and eventually as a high-achieving college athlete. In the eventful summer of 1968 Bill Hurd was on the starting block of greatness, a member of the finest generation of American sprinters ever. Hurd first came to public attention in 1965 as a senior at Manassas High School, when he ran a 100-yard race in 9.3 seconds at the old Fairgrounds, destroying the existing record, which had been held for over thirty years by the legendary Jesse Owens. Hurd trained in the worn grass and white-hot cinder of Tully Street in the North Chicago neighbourhood that fed Manassas High, and he came to dominate high-school athletics in Mississippi throughout his teenage years. Like a character from television drama, he ran the streets to and from home, carrying a battered saxophone case and dreaming of greatness. The trophies and medals he brought home with him went on proud display in a glass cabinet at his family home and his saxophone lay next to him by his bed.

For three years as a teenager, Hurd had played out a local rivalry with Melrose High School sprinter Willie Dawson, from Orange Mound. It was a rivalry that bewitched the Memphis press and drove both boys to the fringes of international recognition. Both were offered university scholarships and invited to compete in the US Olympic trials, having dominated competition in the Mid-South. Hurd had his mind set on attending Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but was targeted by coaches in Indiana and eventually accepted a scholarship from Notre Dame, becoming one of the few black students on the prestigious campus. Hurd’s best

event was the rarely run 300-yard dash, in which he set an American indoor record of 29.8 seconds, but he also ran a 6-seconds dead 60-yard sprint, when the world record was 5.9 seconds. In 1968 he clocked up impressive times across all the sprint categories and was invited to join the Olympic track and field squad for their trials at Echo Summit, in Lake Tahoe, California, where new and profound challenges awaited him. Perhaps mistakenly, Hurd had no clear sprint specialism and elected to run in the most competitive category of all – the unforgiving 100-yard sprint, where the margin between winning and losing was measured by a hair’s breadth.

Lake Tahoe was situated on a mountain pass, 7,000 feet above ground level, with a track carved out of the mountainside, and was chosen as the preferred venue because it replicated the high-altitude thin-air conditions expected at the forthcoming Olympic Games in Mexico. The complex had been fitted with a revolutionary ‘tartan track’, the first generation of synthetic surfaces. It was a surface that suited Hurd, and as a five-time All-American sprinter, who had shattered nearly every record on Notre Dame’s athletic roster, he was seen from the outset as a strong contender to make the Olympic team. But the competition was unprecedented and unforgiving. Hurd found himself up against the greatest generation of sprinters the USA has ever produced. The warning signs were obvious on the night of 20 June 1968 at the US National Championships, at a meeting that track historians have since dubbed ‘the Night of Speed’. The competition was awe-inspiring. Among their number were: Jim Hines from Oakland, California, the first man to smash the 10-second barrier for the 100 metres; Charles Greene from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the reigning American Athletic Union champion; Tommie ‘The Jet’ Smith aka the Clarksville Kid, who had overcome pneumonia and childhood disability to become the fastest man in the world over 200 metres; and the Harlem-born Cuban-American John Carlos, who unexpectedly beat Smith in the trials, but had his world record nullified for wearing unregistered brush spikes. In the 400-metres category was Lee Evans, a runner Hurd had never faced nor met, but their records were nearly identical: unbeaten at high-school level, high academic achievers, and then in Evans’ case the offer of a prestigious athletics scholarship that led to a Fulbright. Records tumbled like decaying trees. Over ten intense days of competition, the trials produced two hand-timed world records: one for John Carlos in the 200 metres and another for Lee Evans in the 400 metres; while the spidery Bob Beamon, soon to smash the world long-jump record in the thin air of Mexico, equalled what was then the standing world record. In one day, four world records were broken in what were only the trials.

Hurd ran a time that would have easily qualified him for almost every other country in the world but he was eventually squeezed out of the time-dominated 1968 Olympic team by 0.1 seconds. He ran 10.2 in the 100 metres, the same recorded time as another rival Mel Pender, who qualified in front of him and eventually went to Mexico where he won gold in the 4x110 metres relay team. Hurd’s life was changed in that fraction of a second, and he returned to a successful season in collegiate sports, out of the Olympics in the blink of an eye. It was a bitter disappointment, but over the few days he spent in Lake Tahoe Hurd began to sense that something quite spectacular was afoot. He became aware of the anger that was growing among the elite athletes of the day. The US athletics chiefs had been measuring speed and distance using the most sophisticated mechanisms available to them at the time but they had not measured the political temperature or the deep feelings of resentment that were festering within the camp.

Success and circumstance had conspired to bring a generation of militant athletes to the Olympics, a group of supremely self-confident young black men who were unlikely to concede to any form of discrimination. Throughout the trials at Lake Tahoe, Hurd listened as his rivals discussed civil rights and the vagaries of sport and politics long into the night. He played his saxophone back in the dormitories, offering virtuoso jazz solos to the assembled athletes. Among them were Tommie Smith and John Carlos, founding members of the controversial Black Power organisation the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). OPHR was an organisation of major athletes committed to combating racism in athletics, segregation in the USA and apartheid in South Africa. For a tense period in 1967, the group had threatened to boycott the Games of the XIX Olympiad, leaving the US Olympics body with the prospect of either withdrawing from competition or having to accept the humiliating prospect of fielding an all-white team. The idea for a boycott had been hatched by former sports star turned professor of sociology Harry Edwards, who, when he taught at San Jose State University, had come to realise that black students were discriminated against in campus housing provision. Some of his best black athletes were allocated rooms at the furthest distance from the campus facilities. One of Professor Edwards’s students, the sprinter Tommie Smith, took up the cause. The campaign soon diversified into a sporting movement. Hurd first heard of the campaign from a fellow student at Notre Dame and became a cautious supporter. He was eager to make the Olympic team, but since his school days at Manassas High he had grown up in an area where civil rights campaigns were commonplace.

The OPHR had its first major success when the towering basketball prodigy Lew Alcindor, who later changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar after converting to Islam, joined the fray. At the time Alcindor was collegiate box office. From his freshman year at UCLA, the seven-foot-two Hoops giant was the likeliest candidate to join the professional NBA as first-choice draft pick. Alcindor was a Catholic who had been the star player in a New York Catholic basketball league, but as he read and witnessed change in the world he converted to Islam and announced his decision to join the Olympic boycott movement at a game in Los Angeles. Alcindor told the crowd: ‘I’m the big basketball star, the weekend hero, everybody’s All-American. Well, last summer I was almost killed by a racist cop shooting at a black cat in Harlem. He was shooting on the street – where masses of people were standing around or just taking a walk. But he didn’t care. After all we were just niggers. I found out last summer that we don’t catch hell because we aren’t basketball stars or because we don’t have money. We catch hell because we are black. Somewhere each of us have got to make a stand against this kind of thing. This is how I take my stand – using what I have. And I take my stand here.’ The crowd erupted in approval, the first time the movement had attracted popular support. Alcindor paved the way for others, and in the days prior to his assassination the movement elicited the support of Martin Luther King, who said, ‘No one looking at these . . . demands can ignore the truth of them . . . Freedom always demands sacrifice.’

Not everyone agreed, even among prominent black athletes. The conservative-minded heavyweight boxer Floyd Patterson, usurped by Muhammad Ali at the time, refused to support the campaign; and O.J. Simpson, originally an international-class track athlete and running back at the University of Southern California – and poised to be the most expensive athlete in the world in the 1969 draft – said the campaign did not matter much to him and declined to participate.

The OPHR had five central demands: to restore Muhammad Ali’s title after his refusal to join the draft and fight in Vietnam; to remove the white supremacist Avery Brundage from his role as head of the United States Olympic Committee; to exclude apartheid regimes in South Africa and Rhodesia from international sporting competition; to increase the number of black coaches hired by colleges and professional teams; and to boycott the selective whites-only New York Athletic Club.

All of the movement’s key demands were discussed in the feisty and cloistered environment of the US trials. Hurd shared some of his experiences with his rivals, talking about events back home in Memphis and his own role in organised campus protest at Notre Dame. He was one of only twelve black freshmen back in 1965 when he led a campus-wide protest against a visiting speaker, Senator Storm Thurmond, the notorious segregationist and vociferous opponent of civil rights. In a failed attempt at the presidency, Thurmond had once said: ‘I wanna tell you, ladies and gentlemen, that there’s not enough

troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Nigra race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches.’ Paradoxically, as a young man he had impregnated the family’s black maid and had a mixed-race daughter who he secretly funded through a black college. Hurd and a small group of supporters from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) harangued Thurmond throughout his visit to the Notre Dame campus.

Memphis 68

Memphis 68